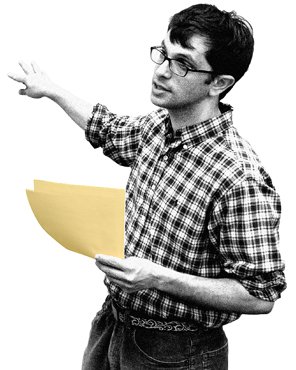

People studying public-health issues must cope with surprisingly shoddy data. Plenty of numbers are available, but epidemiologists and policy makers often don’t trust them, because they are frequently incomplete, inconsistent, and inaccurate. “When I came to global health, I was shocked by how little we knew,” says mathematician Abraham Flaxman, an assistant professor of global health at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington.

In response, Flaxman has developed improved models and algorithms that can automatically fill in the gaps in flawed health data. His breakthrough approach, which is now widely used, came from a realization that improving the quality of a large data set requires not just analyzing it on its own but also cross-analyzing it against other relevant data sets that have at least some variables in common.

Flaxman started off as a postdoctoral fellow with Microsoft Research’s Theory Group, where he studied complex networks, but he soon yearned to apply his mathematical and modeling skills to big health problems. When he made the jump to academia, he immediately discovered that public health was beset by serious data problems, and he began trying to address those problems.

Flaxman is using his methodology to track the spread and treatment of a wide range of diseases. His latest model, called DisModIII, starts with all the available data on the incidence and mortality of a specific disease. It then integrates and cross-analyzes the data to produce consistent estimates of the way the disease progresses through a population as a function of age, time, gender, and geography.

About 800 researchers use DisModIII to track more than 140 diseases, including hepatitis B and cholera. Researchers and policy makers had long dealt with data that had to be taken on faith and data analysis tools that were unique to each disease. Applying Flaxman’s one tool to different data sets covering many different diseases provides credible, apples-to-apples comparisons of their relative impact. That helps policy makers direct health funds to the interventions likely to save the most lives.

Flaxman continues to come across new areas in which his modeling approaches can play a pivotal role. One of them is determining causes of death. Death certificates in developing countries are often incomplete or inaccurate—if they exist at all. The conventional approach is to collect information about symptoms and other matters from relatives and friends of the deceased person, and have a physician review the results to make an educated guess—a labor-intensive technique called a “verbal autopsy.”

Flaxman created a computer program that examined available information about a wide range of deceased people whose causes of death were known in order to come up with accurate correlations between observations and causes. Now the software can determine causes of death far more cheaply than physicians can conduct verbal autopsies, getting it right more often as well.

Flaxman wants to do much more to improve health data; he’s driven by the knowledge that the policy and public-health decisions informed by his tools are matters of life and death on a large scale. “These are data that really matter,” he says.

—Dwight Davis